In 1973, an agricultural program aimed at solving the country’s then-worsening rice shortage was developed. It was called Masagana 99, after the Filipino word for “bountiful” and the target number of cavans per hectare of rice to be produced under the program.

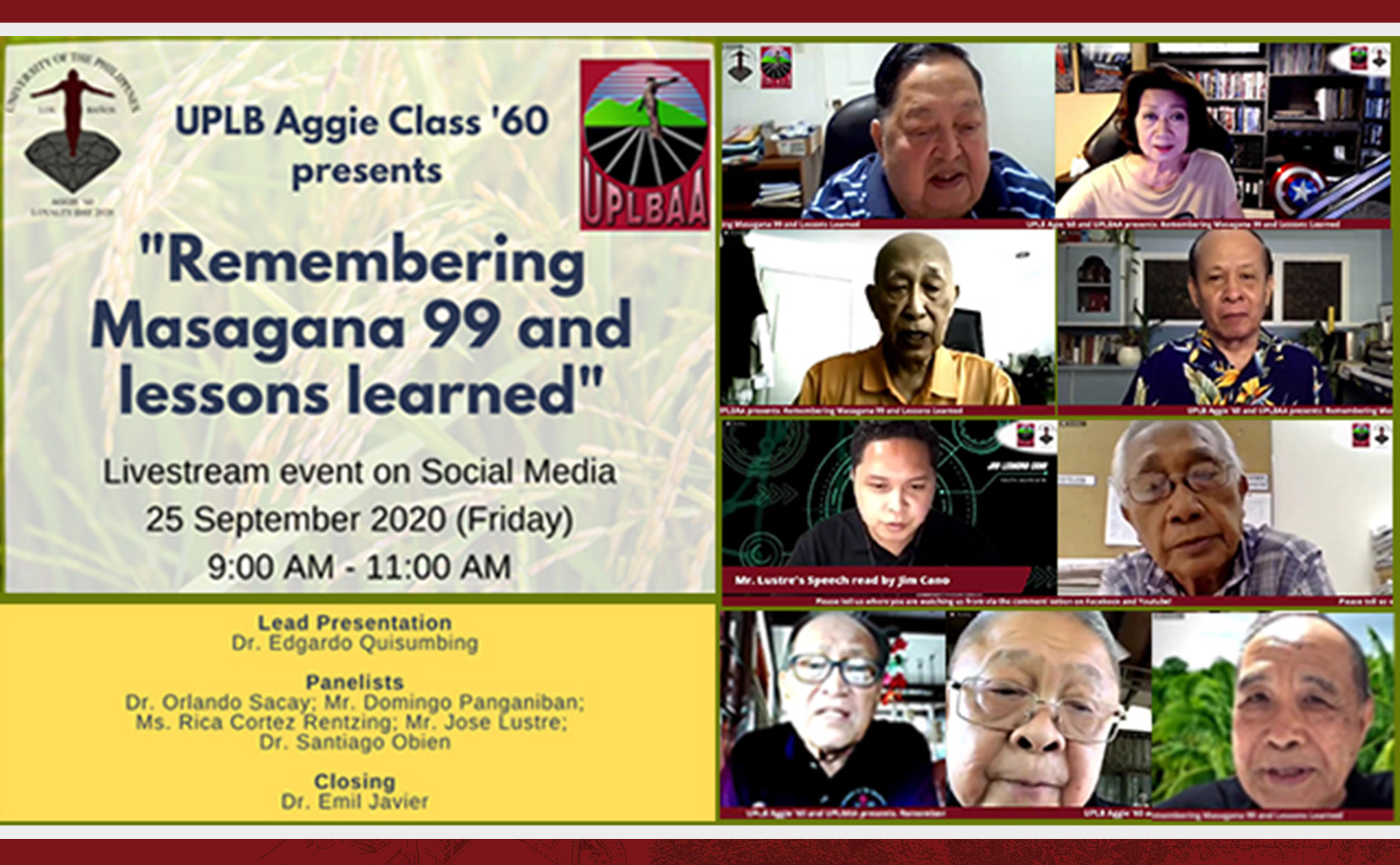

Its success and failure served as the centerpiece of a webinar that the UP College of Agriculture Class of 1960 staged on Sept. 25 as a part of a webinar series to celebrate the UPLB 102nd Loyalty Day.

A panel of agriculturists, scientists, and personnel who were part of the Masagana 99’s initial implementation discussed this agricultural program.

According to Dr. Edgardo Quisumbing, former deputy implementer of the program, Masagana 99 was at its core, an emergency program in response to the severe rice shortage due to pests and natural disasters occurring at the time.

He recalled that the government tapped the country’s academics and scientists, many from UPLB, to create and help implement the program that was essentially a technology package for farmers.

This package, he said, was made up of high-yielding rice varieties and low-cost pesticides and fertilizers, alongside a supervised credit scheme that enabled the farmers to purchase the said technology.

Scientific research and technology played important roles in the program, according to Dr. Santiago Obien, founding executive director of the Philippine Rice Research Institute and current National Rice Program senior technical adviser.

He noted that Masagana 99’s key strategy to increase rice production was not through the traditional method of expanding the planting area, but by increasing the yield per hectare. This was achieved through using high-yielding varieties of rice and low-cost but highly effective pesticides and fertilizers.

Dr. Obien said that although the program had its share of problems, it was successful in both “producing enough food at that time, and in averting some potential social problems.”

Rica Cortez Rentzing, then an executive assistant of Agriculture Secretary Arturo Tanco, talked about how the Masagana 99 agricultural technicians were able to identify with the latter. She emphasized the importance of political will in implementing Masagana 99.

Former Agriculture Secretary Domingo Panganiban, who was then a field-level implementer of Masagana 99, looked back at the farmers’ initial distrust of government until they realized that it was serious in helping them, especially when the agricultural technicians taught them the technologies.

Panganiban said, “the program collapsed because they forgot about the small farmer, (and) replaced the technicians with non-agriculturists.”

Dr. Orlando Sacay, former National Anti-Poverty Commission secretary-general who is known as the father of Philippine cooperative banking, also noted that while the Masagana 99 was good, it was not sustained and its credit program was concerning and problematic.

Jose Lustre, a rural banker for over fifty years, talked about the experience of rural banks under the program in his prepared speech read by webinar co-moderator Jim Leandro Cano, a teaching associate at the College of Agriculture and Food Science.

Lustre said that rural banks shouldered the risk of giving loans to the farmers for the program. The collection for the repayment of those loans, he said, gradually dropped from 90% in the earlier phases of the program to 35% and lower in the latter phases, which then had severe consequences for the rural banks.

At the end of the recollections and stories, the panelists agreed that the program was both a success and a failure. Going by its stated purpose of resolving the rice shortage at the time, they said that Masagana 99 was a rousing success.

However, they said that its unsustainability and issues such as the problematic credit system, use of pesticides that were damaging to the environment, and loss of properly-trained personnel, served as important lessons that should be taken into account for future programs.

The low loan repayment, problematic implementation, and rising farmer debt led to the program becoming inconsequential by 1980, until it quietly stopped in 1984.

National Scientist Emil Q. Javier, who is a member of Class ’60, concluded the webinar.

“The narrative that the Filipino cannot rise above mediocrity is not correct, and we don’t accept that, because in Masagana 99, we succeeded, and the successor programs of Masagana 99 built upon it and solved many of the deficiencies and flaws,” he said.

The webinar was hosted by Dream Agritech via Zoom, with simultaneous livestreaming on Facebook and Youtube.

Class 60’s Dr. Ruben Villareal, former UPLB chancellor, served as webinar co-moderator, and Dr. Rogelio Cuyno, former UP Mindanao chancellor, as the master of ceremonies. (Albert Geoffred B. Peralta)